Ride London: How to fuel for a 100-mile bike ride

Updated 19th July 2019

This year’s Prudential RideLondon-Surrey will see around 100,000 amateur cyclists take to the streets of London in the UK’s biggest festival of cycling. It includes a number of road races for professionals but keen riders will also be taking part in the sportive event: a 100-mile ride from London to Surrey on a similar route to that of the London 2012 Olympic Road Cycling race. So how do you fuel your body before, during and after an event like this?

Avoid ‘bonking’

The key is to start the ride with full stores of glycogen (carbohydrate). This will not only help fuel your leg muscles and increase your endurance but will also reduce the chances of you ‘bonking’. This is the cycling term for that terrible feeling when you’ve nothing left in the tank: your legs turn to jelly, you feel weak, dizzy and disorientated and can no longer keep pedalling. It happens when you have depleted your body’s glycogen stores.

It’s hard to get back from a ‘bonk’ so your best protection is to ensure that your glycogen is fully topped up before starting and then to refuel throughout the ride. The former is achieved by carbohydrate loading – tapering your training during pre-ride week and increasing your carbohydrate intake. The ACSM recommend 10 – 12g carbohydrate/ kg of body weight per day in the last 48 hours before the event (700 – 840g/ day for a 70kg cyclist).

That may sound a lot but, in practice, you simply need to ensure you include a decent-sized portion of high-carb foods such as porridge, potatoes, pasta, rice, bread, fruit and pulses in each of your meals. But don’t take it to extremes and eat too much, otherwise you may wake up feeling heavy and bloated on event day. Carb loading doesn’t mean eating as much as you can!

The day before

Stick to the foods you normally eat and don’t experiment with anything new. Eat plain and simple meals, including a portion of carbohydrate and a portion of protein. A simple tip is to eat most of your food at breakfast and lunch rather than a big meal late in the evening. Little and often will help maximise glycogen storage. And keep hydrated – sip on water frequently throughout the day.

Try to minimise fibre (e.g. by swapping wholemeal for white bread) and steer clear of anything that may cause digestive issues and jeopardise your performance. On the other hand, if you’re fine with these foods, then there’s no need to avoid completely. Suitable meals include a chicken or chickpea tagine (stew) with couscous, Pad Thai (noodles) with tofu or chicken, or a simple risotto with butternut squash, beans and peas

The morning of the ride

If you’re doing RideLondon, you’ll have an early start so may not feel like eating breakfast at 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning! However, eating something rather than nothing beforehand will help delay the onset of fatigue and means you’ll feel better during the ride. How much and what you eat before the ride will depend on how much time you have between waking and the start of the ride. The less time you have before your ride, the smaller your meal should be.

Have a breakfast you’re used to. This should contain foods rich in carbs and protein to help keep you satiated. If you are able to eat at least 2 hours before riding, try porridge with fruit and nuts; overnight oats (or Bircher muesli) or granola with fruit and yogurt. If you have less than 2 hours or you simply can’t face a meal, opt for an oat bar, banana or smoothie. It’s important to start the ride hydrated, so sip water frequently and aim to drink 350- 500ml fluid 2 – 3 h before you start riding.

Many cyclists like to include coffee for a pre-ride caffeine boost. But not everyone responds well to caffeine (it may cause trembling and headaches), so don’t try it for the first time before an event. In studies, it’s been proven to increase alertness and lower perception of effort, making cycling feel easier and increasing endurance. The current consensus is approx 1 – 3mg/ kg body weight, that’s equivalent to a double espresso but you may prefer pills, gels or chews.

During the ride

Start refuelling within the first hour or so, and then refuel every 30 – 60 minutes, aiming for a total of 30 – 90g carbohydrate/ hour. The exact amount you need depends on how hard you’re riding. For example, cycling fast or uphill burns proportionally more carbohydrate than fat compared with cycling at a leisurely pace or on the flat, so you’ll need consume more carbs during these stages. You can get 30g carbohydrate in the following:

-

- 1 large banana

- 40g (a small handful) dried fruit

- 1 Oat bar or 2 Nakd bars

- 500ml sports drink (6% carbs)

- 1 energy bar

- 4 energy chews

- 1 energy gel

Refuelling during the ride helps maintain blood glucose levels within an optimal range and supply additional fuel to your muscles. This reduces the rate at which your muscles burn glycogen and thus helps stave off fatigue.

Take high-carb snacks that you have trained with, including savoury options (e.g. peanut butter or Marmite sandwiches, rice cakes and pretzels) as well as sweet to reduce flavour fatigue and the risk of tooth damage. You may want to take natural foods (e.g. fruit and nut bars, bananas, flapjacks and dried fruit) as well as energy products (e.g. gels and bars), whatever you’ve trained with. Use natural food nearer the start to give it time to digest, energy products nearer the end when you need a quick boost. Prepare as much as possible e.g. cut bars in half and open wrappers to make them easier to consume, and put them in your pockets. If you wish, you can use caffeine during the ride to make it feel easier, increase focus and reduce fatigue – but only if you’ve used it successfully in training.

Take two refillable bottles: one for water and one for a sports or electrolyte drink (or whatever you used during training). Your aim is to avoid under-drinking (dehydration) as well as over-drinking (hyponatraemia). Drink little and often and to thirst; the amount you need depends on your sweat rate, which will increase during hot humid weather and on climbs. Aim for approximately 400 – 800ml/ h. Drinks containing electrolytes are recommended on long hard rides over 2 hours or when sweat losses are high (especially if you’re a salty sweater).

Check in advance where feeding and drinks stations are on the route. Use the opportunity to re-fill your bottles and stock up with food – but avoid over-eating! Be wary of trying new products – stick to what you’ve trained with.

Recovery

When it’s all over, following a few simple rules for recovery will help you feel better in the following few days. Sip water or a sports or electrolyte drink – rehydration can take up to 24 hours so continue drinking frequently. You’ll need carbs and protein to refuel your glycogen and repair damaged fibres in your muscles. Good options include milk-based drinks, recovery drinks, cheese sandwiches, yogurt, protein bars, flapjacks and bananas. Then go ahead and celebrate! Suitable recovery meals include rice and fish, or sweet potatoes with cheese or hummus and salad.

If you want more advice..

I’ll be on Centre Stage at the 2019 Prudential RideLondon Cycling Show, giving five talks each day with lots of simple, practical tips. The Show is free to enter, open to all and runs from Thursday 1st August until Saturday 3rd August.

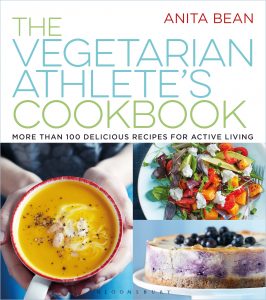

If you enjoyed this post and want to find out more about food and nutrition, as well as some easy and tasty meal inspiration, then The Vegetarian Athlete’s Cookbook – More than 100 recipes for active living (Bloomsbury, 2016) is a great place to start. It features:

If you enjoyed this post and want to find out more about food and nutrition, as well as some easy and tasty meal inspiration, then The Vegetarian Athlete’s Cookbook – More than 100 recipes for active living (Bloomsbury, 2016) is a great place to start. It features:

More than 100 delicious, easy-to-prepare vegetarian and vegan recipes for healthy breakfasts, main meals, desserts, sweet and savoury snacks and shakes.

- Expert advice on how to get the right nutrients to maximise your performance without meat

- Stunning food photography

- Full nutrition information for each recipe, including calories, carbohydrate, fat, protein and fibre

More than 100 delicious, easy-to-prepare vegetarian and vegan recipes for healthy breakfasts, main meals, desserts, sweet and savoury snacks and shakes.

More than 100 delicious, easy-to-prepare vegetarian and vegan recipes for healthy breakfasts, main meals, desserts, sweet and savoury snacks and shakes.