Time Restricted Eating (TRE), a form of intermittent fasting where you limit the time you can spend eating, is one of the hottest diet trends in 2019. It’s touted as an easy way to lose or manage weight and boost health, but does it really work and could it hinder your performance?

The idea behind TRE is that aligning your eating to your circadian rhythm (internal body clock) – shortening the window of time in which you consume your day’s food – reduces your risk of chronic disease. In essence, it involves eating within a window of 12 hours or less – a much smaller time frame than many people are used to. This effectively extends the period overnight when you are ‘fasting’, or not eating.

The problem is that our 24-hour lifestyle – grazing throughout the day, eating late at night, working shifts – is out of sync with our circadian rhythm, which researchers say puts us at greater risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes and heart disease.

What’s clear is that our bodies are designed to digest and absorb food most efficiently during a relatively short period of each day; then repair itself and burn stored fat when we fast. When we eat over an extended period – 12 hours or longer – our bodies cannot fully carry out the natural repair processes in the liver, gut and other organs.

What is the evidence?

Most of the studies to date have been done with fruit flies and mice. One study (and this one) found that mice that only ate within a defined period each day lost weight and had healthier blood sugar and cholesterol levels even when they were fed exactly the same food and same calories as mice given free access to food.

But the evidence with humans is scant. Its early days but researchers at the Salk Research Institute for Biological Studies in California, US, found that when people cut their eating window from 14 hours to 10 – 11 hours, they lost an average 3kg over 16 weeks without consciously changing what they ate. Another US study showed similar results but no further weight loss benefits when people cut down to an 8-hour eating window.

A pilot study at the University of Surrey, found that people who delayed their usual breakfast time by 90 minutes, and brought their usual dinner time forward by 90 minutes for 10 weeks lost more body fat than those who ate to whatever schedule they liked.

It’s not known at the moment whether there is an optimum window or how critical timing is. However, a recent study suggests that an early eating window (8am to 2pm) may be advantageous as it reduces appetite and subsequent food intake. This echoes the findings from a US study, which also found that eating within a 6-hour window before 3pm decreased daily swings in hunger as well as lowered type 2 diabetes risk factors (e.g. insulin sensitivity) in men with pre-diabetes.

In practice, when people reduce their eating window, they tend to eat less food. This happens mainly because they have fewer opportunities to eat, particularly in the evening when they’re more likely to ‘graze.’

Bottom line

Eating within a roughly 10 – 12 hour window may have health benefits in terms of insulin sensitivity and weight management but it is certainly not a miracle weight loss diet. If it suits your lifestyle and helps you adopt healthier eating patterns in the long term (i.e. not eating late in the evening or at night), then it may be a good option.

But I do have reservations about TRE. First, I don’t believe it is appropriate for athletes, particularly those with high energy demands, those who train twice a day and anyone undertaking a hard training block as it wouldn’t allow you to refuel and recover properly. Competitive swimmers, for example, often train at early in the morning and again late in the evening. Eating within a narrow window certainly isn’t realistic for them. I feel there is a very real risk that TRE could result in energy deficiency (RED-S), and have an adverse effect on health and performance.

Second, I fear TRE could leading to unhealthy eating behaviours and disordered eating. There’s a trend for hardcore types to push TRE to 16:8 or 20:4, increasing the amount of time spent fasting and decreasing the eating window. Such practices are not evidence based. I foresee TRE being used by some as a socially acceptable excuse for food restriction, skipping meals and dangerous dieting. I hope that I am wrong.

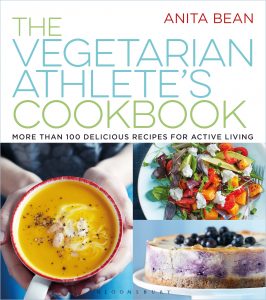

If you enjoyed this post and want to find out more about food and nutrition, as well as some easy and tasty meal inspiration, then The Vegetarian Athlete’s Cookbook – More than 100 recipes for active living (Bloomsbury, 2016) is a great place to start. It features:

If you enjoyed this post and want to find out more about food and nutrition, as well as some easy and tasty meal inspiration, then The Vegetarian Athlete’s Cookbook – More than 100 recipes for active living (Bloomsbury, 2016) is a great place to start. It features:

More than 100 delicious, easy-to-prepare vegetarian and vegan recipes for healthy breakfasts, main meals, desserts, sweet and savoury snacks and shakes.

- Expert advice on how to get the right nutrients to maximise your performance without meat

- Stunning food photography

- Full nutrition information for each recipe, including calories, carbohydrate, fat, protein and fibre